- Home

- Beverly Jenkins

Rebel

Rebel Read online

Dedication

Dedicated to the real Valinda for her support of education, history, and the romance genre

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Author’s Note

About the Author

By Beverly Jenkins

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One

April 1867

Twenty-eight-year-old Valinda Lacy greeted her fifteen students with a smile as they filed into her classroom. Due to New Orleans’s post-war chaos, she was teaching out of an old barn a few miles from the docks and warehouses on the Mississippi River.

Offering smiles and words of greeting in return, some of the students took seats on the rough-hewn bench at the back of the room, while the rest made themselves comfortable on the clean-swept dirt floor. Her pupils varied in both age and gender but had one thing in common. They were former slaves, freed by the South’s surrender. Now they wanted to learn to read and write in hopes of bettering their futures.

“Did you get a chance to practice writing your names?” Val asked from behind the small listing table that served as her desk at the front of the room.

Many nodded affirmatively. Since the school opened a month ago, most had learned to recognize and pronounce the letters of the alphabet and write their names. She was now guiding them in the basics of reading simple one-syllable words like cat, hand, and fish. The excitement they expressed upon mastering the tasks put tears of pride in their eyes and joy in her heart.

However, like most of the schools dedicated to the recently freed, there weren’t enough books, slates, or other supplies necessary for a well-stocked classroom, but Val made do with what she had.

She was passing out her five precious copies of the McGuffey primer when two White men appeared in the doorway. Everyone in the classroom froze. Val dragged her attention away from the long guns they were carrying, drew in a deep breath to tamp down her uneasiness, and met their hard eyes. Many schools serving the freedmen were being burned to the ground by supremacists, their teachers murdered. She didn’t want to be next.

“May I help you?”

“You the teacher?” one asked contemptuously. Both were of medium height, unshaven and dressed in clothes that hadn’t been new in quite some time.

“I am. Welcome to our classroom. We usually begin our day here at nine, so please try and be prompt. If you’ll leave your guns outside, we’ll kindly make room for you to sit and join us. Can you read?”

A flush rose up their necks.

“There’s no need to be embarrassed. We’re all here to learn. I teach children two days a week also, so if you have little ones, they are more than welcome to join us, too.”

One of the men opened his mouth to speak, but she didn’t let him. “I’ll need your names so I can add you to the rolls. The Sisters of the Holy Family sponsor this school. Did you hear about us through them?” She waited, saw bewilderment pass between them, and added, “Never mind. How you heard about the school doesn’t really matter. But I do need your names.”

She walked back to her desk and picked up a pencil and a piece of paper. “I’m always pleased to welcome new learners. Being able to read and write proficiently can impact your future in many positive ways, but I’m sure you know that. Otherwise you wouldn’t have come.”

They stared as if she were a talking horse.

“Please, have a seat.” She gestured, smiling falsely. “We don’t have enough books but we’re accustomed to sharing here.”

The men glanced around at the angrily set faces of the men and women in the room and stammered. “Uhm. We need to go.”

And they left in haste.

In the silence that followed, Val dropped into her chair and let the fear and tension drain away. When she looked up, her students were smiling, and she smiled, too. Forty-two-year-old Eb Slayton called out, “Miss, you had them so confused they didn’t know General Sherman from their mamas.”

And everyone burst into laughter. Val laughed, too, but inside knew they’d been lucky the two had been so easily baffled. She hoped that luck continued.

Two hours later, Val dismissed her class. Many of the students drifted away to return to jobs and families, but others like seventeen-year-old Dina Watson lingered.

“What’s it like living up North, ma’am?”

Val placed the five McGuffey readers into the small strongbox for safekeeping and glanced to the young woman. “The weather’s certainly cooler,” she replied. For a Northern-born woman, being in the New Orleans heat was akin to walking into a foundry furnace. She was right now roasting in her attire of proper long-sleeved, high-necked blouse, flowing skirt, and hose.

“You’ll get used to it,” the smiling Dina promised. “Are our people there free?”

Val nodded. “In New York where I’m from, since 1827. Almost fifty years.” Seeing Dina’s surprise, she added, “But it isn’t true freedom. We’re still unable to vote or own property in many places. Social mixing is frowned upon, so we have our own schools, churches, and businesses. Some communities even have their own newspapers.”

“Your parents free, too?”

“Yes. My grandmother Rose ran when she was about fourteen.”

“From where?”

“Virginia. She first went to Philadelphia, then to New York and opened a seamstress shop. My father’s parents escaped from Charleston when he was an infant.” And unlike Rose, her father was embarrassed by his slave birth and spent his life claiming he’d been born free.

“You got somebody you sweet on back home?”

Val thought about her intended with a deeply felt fondness. “Yes, his name is Coleman Bennett. We’ve known each other since we were children.”

“Is he in New Orleans with you?”

“No, he and his business partner are in France seeking financial support for their newspaper.” They’d be back in the States soon. She missed him and could’ve used his support in her battle with her father over her desire to travel to New Orleans to teach. In the end, she was allowed to go until Cole’s return. Her time in the city would undoubtedly be shorter than she wanted, but in dealing with her father, she’d learned to take victory where she could.

“The French built New Orleans.”

Pleased with Dina’s knowledge of that fact, she said, “Yes, they did.” In addition to the Spanish, and an influx of Haitians who’d fled the island after the revolution there.

Eb Slayton stuck his head in the door. “You ready to go, ma’am? I don’t want to be late for work.” He often gave Val a ride back to the Quarter after class ended.

“Yes. Dina, be careful going home. I’ll see you on Thursday.”

“I will.”

School was held on Mondays and Thursdays. Val devoted the other days of the week to teaching freedmen children at the convent of the Sisters of the Holy Family, one of the few orders in the nation run by nuns of color. Val picked up her worn brown leather satchel and took one last look around at the neatly swept, makeshift classroom. She was proud to have such a space and even prouder of her eager and focused students. Closing the door, she secured it with the padlock and joined Eb on the seat of his rickety wagon.

Even though it wou

ld take his old mule, Willie, some time to get them to the Quarter, she preferred that to being at the mercy of the city’s segregated streetcar system. Men and women of the race could only ride cars bearing black stars on the side. Whether intentional or not, there were never enough vehicles to be had, they didn’t keep a consistent schedule, and because Whites could ride them, too, gangs of toughs often filled them to purposely make them overcrowded and to harass Black women going back and forth to work.

“I liked the way you handled the Cranston brothers,” Eb said to her as they got underway.

“Those men with the guns? You know them?”

He nodded. “Pete and Wesley Cranston. Before Freedom, their daddy was the overseer on a big sugar plantation west of here. Mean as a snake. He died during the war, and now his boys go around causing trouble trying to be like him.”

“Are they truly dangerous?”

“They can be, but mostly pick on women and old people. Heard they roughed up some of the teachers and missionaries to the point a few went back North. I’m pretty sure seeing the men in the classroom made them think twice about whatever they’d planned to do. I know they didn’t expect you to stand up to them the way you did.”

“My grandmother always told me that no matter how scared you are, never show it.”

“You did her proud. Watching you run circles around them made my day.”

She appreciated the praise. “Do you think they’ll return?”

He shrugged. “There’s no telling. After you dismissed the class, some of the men and I talked about it outside. We’ll be bringing our guns with us from now on. Freedom says we can protect ourselves and we mean to.”

She didn’t care for violence but if it meant she and her students stayed safe, protesting the men’s plan made little sense.

With the issue settled for now, she asked, “Has the Freedmen’s Bureau found your daughter a position?”

He shook his head. “They keep telling her she has nothing official that says she knows how to teach.”

Val sighed. The Freedmen’s Bureau had been established to assist the three and a half million formerly enslaved men, women, and children freed by the South’s surrender. Created over the objections of many in Congress and hampered by sometimes conflicting rules and regulations that varied from state to state, it was a bureaucratic nightmare that ofttimes hindered freedom as much as it assisted. Eb’s daughter, Melinda, had been enslaved by the family of a wealthy college president whose three daughters secretly taught her to read. Having met Melinda last week, Val found her personable and intelligent, and thought her skills would be a blessing in a classroom. “Let her know if she hasn’t found a position soon, she’s welcome to help me here.”

His face brightened. “I sure will.”

Still trying to get the Bureau to pay her the stipend she was owed, Val had no idea how she’d compensate his daughter, but would cross that bridge when she came to it.

Eb then asked, “Do you think you can help my brother put a plea in the newspapers? He’s trying to find his wife.”

“Of course. Have him stop by the school when he can, and we’ll talk it over.”

“Thank you. Since Freedom, he’s been walking plantations in the area looking for her, but so far nobody knows where she is.”

“Does he have children?”

He nodded. “But they were sold years ago to a man in Texas. My brother doesn’t think he’ll ever see them again.”

She couldn’t imagine what Eb’s brother and the thousands of others searching for sold-away family must be going through, but offering her assistance in any way possible was the reason she’d come south. She credited her grandmother Rose for instilling that desire. Rose had been helping to uplift the race in their New York City community for as long as Val had been alive. Whether it was aiding the elderly and poor with food and clothing, attending abolition rallies and marches, or staying after church to read articles from the newspapers published by Mr. Garrison, Mr. Douglass, and Mr. Martin Delany to those who couldn’t, Rose and the women of her circle were who Val aspired to be.

As the slow ride continued, she thought about her own efforts. She’d been in New Orleans for a month now. The city was so different from the strict, staunch confines of New York, it was like being in another country. Music seemed to be everywhere. The women of the race wore headwraps called tignons that could be plain and unassuming, or colorful and decorated with items like beads and cowrie shells. Back home the primary foreign language was Dutch. In New Orleans people spoke French, Spanish, Italian, and all manner of variations in between. New York had its street vendors, but the ones here sold fruits and vegetables she’d never seen or eaten before like okra and sugar cane. She’d come to love the little baked balls of rice called calas that were dusted with sugar and sold in the mornings by women of color. On Sundays, people of the race gathered in a spot called Congo Square, something they’d been doing since slavery. There was music, dancing, and more vendors. She’d never seen anything like it before. Also new to her was the selling of charms and potions that supposedly cast and counteracted spells. The food in New Orleans was rich with cream, seafood, and yeast, and the streets were thick with armed Union soldiers, poor Whites, and crowds of freedmen searching for work. There was also a volatile undercurrent of fury from the former masters who’d lost their way of life. Some of the local newspapers were filled with vitriolic editorials directed at the soldiers and the Radical Republicans. Most alarming were reports of the increasing incidents of violence visited upon the freedmen and their families from terrorizing Lost Cause groups.

Eb halted his wagon in front of the house in the Treme section of the city where Valinda rented a room. She waved goodbye and he and Willie drove off towards the St. Louis Hotel where he worked as a pastry chef. Ironically, at age nine, he’d been sold at a slave auction in the same hotel. She found it hard to reconcile the city’s most famous hotel hosting fancy balls and celebratory dinners while slaves were also being sold under its roof.

Another thing Val found hard to reconcile was her Creole landlady, Georgine Dumas, who shared the home with her older sister, Madeline. Both were elderly but had personalities as different as night and day. Where Madeline was kind and considerate, Georgine was haughty and intolerant. Georgine complained about everything from the weather to Madeline’s cooking, but saved her most acerbic vitriol for the Union soldiers and the newly freed.

“They should ship them all back to Africa,” she declared angrily during dinner the day Val arrived. “They’re as ignorant and useless as the bluecoats.”

Later, Madeline explained that her sister’s anger was rooted in how the surrender changed their lives. Their plantation was gone, as were their slaves, leaving them to do the mundane yet necessary chores tied to living like cooking, cleaning, and the rest. Luckily Madeline knew how to cook. But many of the South’s mistresses hadn’t touched a stove for generations, and now, not knowing turnip from tripe, couldn’t feed their families.

Entering the small flat, Val found Madeline in the kitchen. The fragrant spicy aroma of gumbo cooking filled the space. Val had known nothing about the flavorful stew before coming south but now loved the dish as much as she did the morning calas.

“And how was school today, Valinda?” Madeline asked, putting a lid on the gumbo on the stove and taking a seat at the small table where they shared their meals.

“Good. Two new students showed up, so I now have fifteen. I’ll need to find more spellers somehow. Having the students share makes teaching a challenge.”

“Do you think your grandmother’s church can help?”

“I’ll write her tonight and ask.” Her grandmother’s church back home in New York was her sponsor. In response to a plea for help from the American Missionary Association and the Sisters of the Holy Family, Val and other teachers had traveled south.

They spent a few more minutes talking, and Madeline rose to check on the gumbo. Determining it ready, she called out to her si

ster. Georgine entered and, upon seeing Val, glowered and took her seat.

Madeline said, “You could at least speak to her, Georgie.”

The response was an impatient huff, before Georgine asked Val, “Have the blue bastards paid you yet?”

She replied simply, “No, ma’am.”

“Food and a place to sleep is not free.”

“I understand.”

Madeline spooned the gumbo into bowls, and said tightly, “She’s paying us what she can, Georgie. You know that.”

“I know nothing of the kind. Who’s to say she isn’t giving the money that should be coming to us to those wastrel freedmen?”

Val didn’t reply. The Freedmen’s Bureau was supposed to pay teachers a stipend. Since her arrival a month ago, she’d spent her free time standing in long lines for hours on end only to be told she needed a different requisition form, was at the wrong office, or the person she needed to speak with was unavailable. It was maddening. Having to endure Georgine’s caustic tongue was worse. “I’ll be writing my grandmother to ask if she can send me extra funds so that I may meet my obligations to you and your sister.”

“Otherwise you’ll be asked to leave.”

“Georgie!”

“We can’t afford to keep her here for free, Maddy. She isn’t a pet spaniel.”

“But we promised the Sisters we’d let her stay with us.”

“In exchange for funds. We have no money, Madeline, and no prospect of receiving more. She either pays or she goes.”

Madeline’s voice tightened. “We have money in the bank, Georgie, and you know it. It may not be as much as it was before the surrender, but we won’t starve. You’re just being nasty.”

“You have one week, Miss Lacy.”

Val met the cold black eyes. “Yes, ma’am.”

The meal was eaten in silence. Madeline shot her sister angry glares which Georgine ignored. When they were done, Georgine left the kitchen. Val helped Madeline with the dishes, then sat at the table to begin her letter.

Before exiting Madeline said, “Don’t worry, I won’t allow her to put you on the street.”

On the Corner of Hope and Main

On the Corner of Hope and Main Rebel

Rebel Wild Rain

Wild Rain Forbidden

Forbidden The Edge of Midnight

The Edge of Midnight Something Like Love

Something Like Love A Chance at Love

A Chance at Love Night Song

Night Song Rhythms of Love

Rhythms of Love Captured

Captured Deadly Sexy

Deadly Sexy Night Hawk

Night Hawk Destiny's Captive

Destiny's Captive Heart of Gold

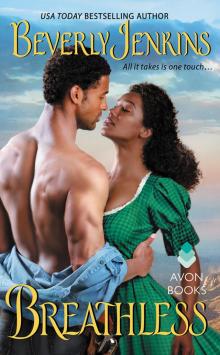

Heart of Gold Breathless

Breathless Crystal Clear

Crystal Clear The Edge of Dawn

The Edge of Dawn Tempest

Tempest This Christmas Rivalry

This Christmas Rivalry Always and Forever

Always and Forever Before the Dawn

Before the Dawn Jewel

Jewel Tempest EPB

Tempest EPB Baby, Let It Snow: I'll Be Home for ChristmasSecond Chance Christmas

Baby, Let It Snow: I'll Be Home for ChristmasSecond Chance Christmas Taming of Jessi Rose

Taming of Jessi Rose Midnight

Midnight Once Upon a Holiday

Once Upon a Holiday Stepping to a New Day

Stepping to a New Day Belle

Belle Josephine

Josephine Indigo

Indigo Second Time Sweeter

Second Time Sweeter A Wish and a Prayer

A Wish and a Prayer Bring on the Blessings

Bring on the Blessings Chasing Down a Dream

Chasing Down a Dream Black Lace

Black Lace Sexy/Dangerous

Sexy/Dangerous You Sang to Me

You Sang to Me A Second Helping

A Second Helping For Your Love

For Your Love Island for Two: Hawaii MagicFiji Fantasy

Island for Two: Hawaii MagicFiji Fantasy Through the Storm

Through the Storm Something Old, Something New

Something Old, Something New Winds of the Storm

Winds of the Storm Destiny's Embrace

Destiny's Embrace You Sang to Me ; Holiday Heat ; I'll be Home for Christmas ; Hawaii Magic ; Overtime Love

You Sang to Me ; Holiday Heat ; I'll be Home for Christmas ; Hawaii Magic ; Overtime Love Merry Sexy Christmas

Merry Sexy Christmas